Note for translation: inspired by C. D. C. Reeve, I reworked Socrates’ reported speech into direct conversation between him and Glaucon.

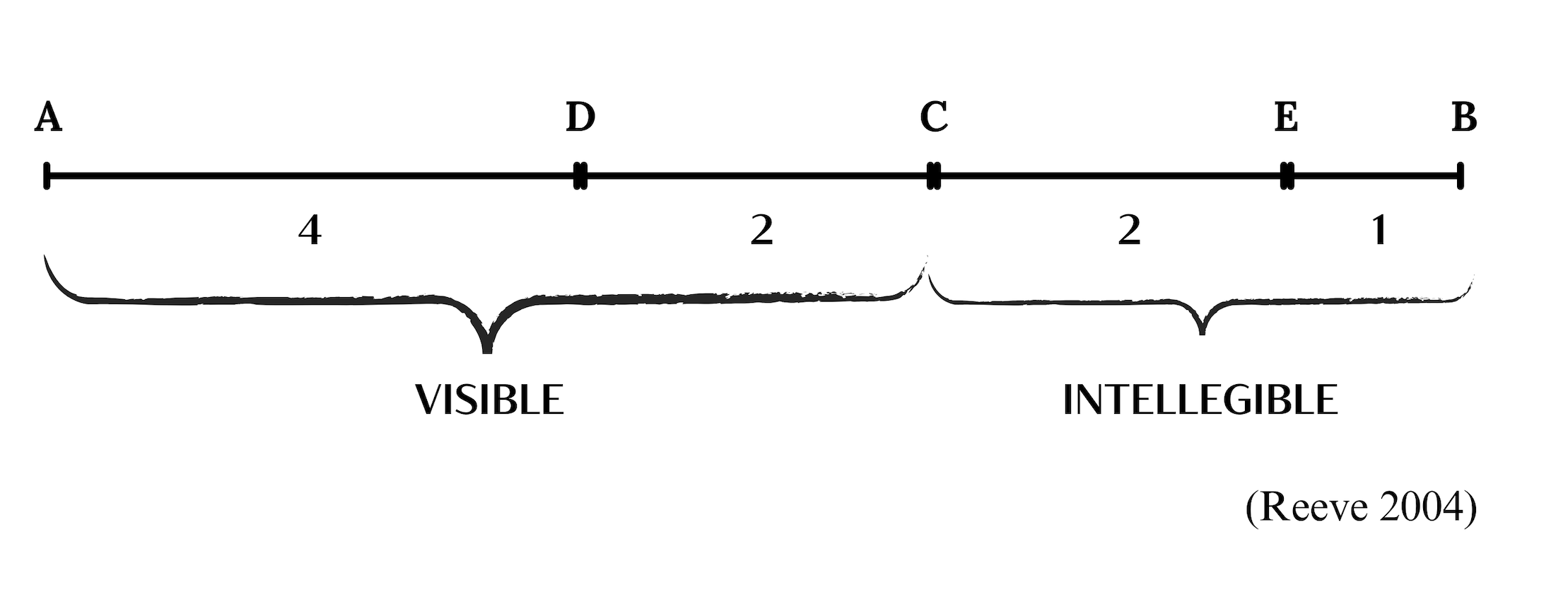

Socrates: Accordingly, consider, just as we are saying, that they are two things and that one rules over intelligible kind and place, another, in turn, visible, in order that I may not seem to you to speculate about the name since having said “of heaven.” But then do you have these two kinds— seen, intelligible?

Glaucon: I have.

Socrates: Accordingly, just as taking a line, after having been cut in two as uneven segments, again cut each segment proportionately, one of the kind being seen and another of the kind being understood, and with respect to clearness and obscurity in relation to one another in, on the one hand, the thing being seen, you have one segment as images— and I speak about the images first, on the one hand, as the shadows, then as the visions in the waters and in the things as many as have existed as close-packed and smooth and bright, and everything of the sort, if you understand.

Glaucon: But I understand.

Socrates: Accordingly, put the other segment as the thing to which this thing is similar, namely, the animals around us and every plant and the whole artificial kind.

Glaucon: I put.

Socrates: Truly you would also be willing to say that it has been divided with respect to truth and untruth, just as the object of opinion in relation to the object of knowledge, in this way as the thing compared in relation to the thing to which it was compared?

Glaucon: I would, at any rate, and very much so.

Socrates: In fact, consider again also the section of the intelligible how it must be cut.

Glaucon: How?

Socrates: As follows: with respect to one of it, on the one hand, soul, by using the things portrayed then as images, is compelled to seek from suppositions, although not going towards a first principle but towards an end. With respect to the other, on the other hand, in turn— the thing not hypothetical towards a first principle— by going from suppositions and without the images about that thing, pursuing its inquiry by means of forms themselves through them.

Glaucon: I did not sufficiently understand these things which you say.

Socrates: But again: for you will understand these things more easily, since having been said beforehand. For I think that you know that the men being engaged concerning the geometries and countings and these sorts of things, by hypothesizing the odd and the even and the shapes and three kinds of angles and other things akin to these according to each method, since knowing these things, on the one hand, using them as suppositions, they still deem it worthy for neither themselves nor others to make any speech about them, since being conspicuous to everyone, and since beginning from these things, now going through the rest, they end by common consent towards that thing of whichever they set in motion towards an inquiry.

Glaucon: Certainly, I know this thing, at any rate.

Socrates: Accordingly, you also know that they use the shapes being seen and make their speeches about them, although not thinking about these things, but about those things to which these things are similar, since making their speeches on account of the square itself and diagonal itself, but not that thing which they grow, and the other things in this way: with respect to these things themselves, on the one hand, with they form an image and draw, of which both shadows and images in waters are, in turn by using these things, on the one hand, as images, seeking, on the other hand, to see those things themselves which someone would not otherwise see than by means of his cognition.

Glaucon: You say true things.

Socrates: Accordingly, I was saying that the form is this intelligible thing, on the one hand, and that soul, since being compelled, uses suppositions concerning the investigation of it, although not going towards a first principle, since not being able to step higher out of its suppositions, by using images themselves, on the other hand, the ones expressed by the things below and those things having been imagined and having been honored as clear in relation to the former.

Glaucon: I understand that you are speaking about the thing under the geometries and the skills akin to this.

Socrates: Accordingly, understand that I say that the other segment of the intelligible is this thing which the logic itself grasps by means of the power of conversing, by making the suppositions not as first principles but truly suppositions, such as stepping stones and onsets, in order that as far as going toward the first principle of every unhypothetical thing, having grasped it, again in turn keeping hold of the things clinging from that thing, in this way it arrives towards an end, in every way using nothing perceptible, but forms themselves through them into them, and it ends in forms.

Glaucon: I understand, not sufficiently for my part—for you seem to me to speak about a difficult work— however, that you want to determine that the part of the thing being and the intelligible being perceived by the knowledge of conversing is clearer than the thing being perceived by the things being called skills, with respect to which the suppositions are first principles and the men viewing are compelled to look at them by thought, on the one hand, but not by perceptions, on account of, on the other hand, not examining by returning towards a first principle but from suppositions, they seem to you to not have sense about them, and indeed, although being intelligible with a first principle. And you seem to me to call the state of the geometrical things and the state of these sorts of things as thought but not intellect, as the thought being somehow between opinion and intellect.

Socrates: You followed most sufficiently. And receive for me these four properties becoming in the soul corresponding to the four segments: understanding, on the one hand, for the highest, thought, on the other hand, for the second, give opinion for the third and likeness for the last, and put them in order proportionately, just as the things for which they exist share in truth, in this way believing that these things share in clearness.

Glaucon: I understand, and I agree and put them in order as you say.

Note: The Greek text below is from:

Plato. Platonis Opera, ed. John Burnet. Oxford University Press. 1903.

Credits to the Perseus Digital Library for digitalizing the work.

[509d] νόησον τοίνυν, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὥσπερ λέγομεν, δύο αὐτὼ εἶναι, καὶ βασιλεύειν τὸ μὲν νοητοῦ γένους τε καὶ τόπου, τὸ δ᾽ αὖ ὁρατοῦ, ἵνα μὴ οὐρανοῦ εἰπὼν δόξω σοι σοφίζεσθαι περὶ τὸ ὄνομα. ἀλλ᾽ οὖν ἔχεις ταῦτα διττὰ εἴδη, ὁρατόν, νοητόν;

ἔχω.

ὥσπερ τοίνυν γραμμὴν δίχα τετμημένην λαβὼν ἄνισα τμήματα, πάλιν τέμνε ἑκάτερον τὸ τμῆμα ἀνὰ τὸν αὐτὸν λόγον, τό τε τοῦ ὁρωμένου γένους καὶ τὸ τοῦ νοουμένου, καί σοι ἔσται σαφηνείᾳ καὶ ἀσαφείᾳ πρὸς ἄλληλα ἐν μὲν τῷ ὁρωμένῳ [509e] τὸ μὲν ἕτερον τμῆμα εἰκόνες—λέγω δὲ τὰς εἰκόνας πρῶτον [510a] μὲν τὰς σκιάς, ἔπειτα τὰ ἐν τοῖς ὕδασι φαντάσματα καὶ ἐν τοῖς ὅσα πυκνά τε καὶ λεῖα καὶ φανὰ συνέστηκεν, καὶ πᾶν τὸ τοιοῦτον, εἰ κατανοεῖς.

ἀλλὰ κατανοῶ.

τὸ τοίνυν ἕτερον τίθει ᾧ τοῦτο ἔοικεν, τά τε περὶ ἡμᾶς ζῷς καὶ πᾶν τὸ φυτευτὸν καὶ τὸ σκευαστὸν ὅλον γένος.

τίθημι, ἔφη.

ἦ καὶ ἐθέλοις ἂν αὐτὸ φάναι, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, διῃρῆσθαι ἀληθείᾳ τε καὶ μή, ὡς τὸ δοξαστὸν πρὸς τὸ γνωστόν, οὕτω τὸ ὁμοιωθὲν πρὸς τὸ ᾧ ὡμοιώθη;

[510b] ἔγωγ᾽, ἔφη, καὶ μάλα.

σκόπει δὴ αὖ καὶ τὴν τοῦ νοητοῦ τομὴν ᾗ τμητέον.

πῇ;

ἧι τὸ μὲν αὐτοῦ τοῖς τότε μιμηθεῖσιν ὡς εἰκόσιν χρωμένη ψυχὴ ζητεῖν ἀναγκάζεται ἐξ ὑποθέσεων, οὐκ ἐπ᾽ ἀρχὴν πορευομένη ἀλλ᾽ ἐπὶ τελευτήν, τὸ δ᾽ αὖ ἕτερον—τὸ ἐπ᾽ ἀρχὴν ἀνυπόθετον—ἐξ ὑποθέσεως ἰοῦσα καὶ ἄνευ τῶν περὶ ἐκεῖνο εἰκόνων, αὐτοῖς εἴδεσι δι᾽ αὐτῶν τὴν μέθοδον ποιουμένη.

ταῦτ᾽, ἔφη, ἃ λέγεις, οὐχ ἱκανῶς ἔμαθον.

[510c] ἀλλ᾽ αὖθις, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ: ῥᾷον γὰρ τούτων προειρημένων μαθήσῃ. οἶμαι γάρ σε εἰδέναι ὅτι οἱ περὶ τὰς γεωμετρίας τε καὶ λογισμοὺς καὶ τὰ τοιαῦτα πραγματευόμενοι, ὑποθέμενοι τό τε περιττὸν καὶ τὸ ἄρτιον καὶ τὰ σχήματα καὶ γωνιῶν τριττὰ εἴδη καὶ ἄλλα τούτων ἀδελφὰ καθ᾽ ἑκάστην μέθοδον, ταῦτα μὲν ὡς εἰδότες, ποιησάμενοι ὑποθέσεις αὐτά, οὐδένα λόγον οὔτε αὑτοῖς οὔτε ἄλλοις ἔτι ἀξιοῦσι περὶ αὐτῶν διδόναι [510d] ὡς παντὶ φανερῶν, ἐκ τούτων δ᾽ ἀρχόμενοι τὰ λοιπὰ ἤδη διεξιόντες τελευτῶσιν ὁμολογουμένως ἐπὶ τοῦτο οὗ ἂν ἐπὶ σκέψιν ὁρμήσωσι.

πάνυ μὲν οὖν, ἔφη, τοῦτό γε οἶδα.

οὐκοῦν καὶ ὅτι τοῖς ὁρωμένοις εἴδεσι προσχρῶνται καὶ τοὺς λόγους περὶ αὐτῶν ποιοῦνται, οὐ περὶ τούτων διανοούμενοι, ἀλλ᾽ ἐκείνων πέρι οἷς ταῦτα ἔοικε, τοῦ τετραγώνου αὐτοῦ ἕνεκα τοὺς λόγους ποιούμενοι καὶ διαμέτρου αὐτῆς, ἀλλ᾽ οὐ [510e] ταύτης ἣν γράφουσιν, καὶ τἆλλα οὕτως, αὐτὰ μὲν ταῦτα ἃ πλάττουσίν τε καὶ γράφουσιν, ὧν καὶ σκιαὶ καὶ ἐν ὕδασιν εἰκόνες εἰσίν, τούτοις μὲν ὡς εἰκόσιν αὖ χρώμενοι, ζητοῦντες [511a] δὲ αὐτὰ ἐκεῖνα ἰδεῖν ἃ οὐκ ἂν ἄλλως ἴδοι τις ἢ τῇ διανοίᾳ.

ἀληθῆ, ἔφη, λέγεις.

τοῦτο τοίνυν νοητὸν μὲν τὸ εἶδος ἔλεγον, ὑποθέσεσι δ᾽ ἀναγκαζομένην ψυχὴν χρῆσθαι περὶ τὴν ζήτησιν αὐτοῦ, οὐκ ἐπ᾽ ἀρχὴν ἰοῦσαν, ὡς οὐ δυναμένην τῶν ὑποθέσεων ἀνωτέρω ἐκβαίνειν, εἰκόσι δὲ χρωμένην αὐτοῖς τοῖς ὑπὸ τῶν κάτω ἀπεικασθεῖσιν καὶ ἐκείνοις πρὸς ἐκεῖνα ὡς ἐναργέσι δεδοξασμένοις τε καὶ τετιμημένοις.

[511b] μανθάνω, ἔφη, ὅτι τὸ ὑπὸ ταῖς γεωμετρίαις τε καὶ ταῖς ταύτης ἀδελφαῖς τέχναις λέγεις.

τὸ τοίνυν ἕτερον μάνθανε τμῆμα τοῦ νοητοῦ λέγοντά με τοῦτο οὗ αὐτὸς ὁ λόγος ἅπτεται τῇ τοῦ διαλέγεσθαι δυνάμει, τὰς ὑποθέσεις ποιούμενος οὐκ ἀρχὰς ἀλλὰ τῷ ὄντι ὑποθέσεις, οἷον ἐπιβάσεις τε καὶ ὁρμάς, ἵνα μέχρι τοῦ ἀνυποθέτου ἐπὶ τὴν τοῦ παντὸς ἀρχὴν ἰών, ἁψάμενος αὐτῆς, πάλιν αὖ ἐχόμενος τῶν ἐκείνης ἐχομένων, οὕτως ἐπὶ τελευτὴν καταβαίνῃ, [511c] αἰσθητῷ παντάπασιν οὐδενὶ προσχρώμενος, ἀλλ᾽ εἴδεσιν αὐτοῖς δι᾽ αὐτῶν εἰς αὐτά, καὶ τελευτᾷ εἰς εἴδη.

μανθάνω, ἔφη, ἱκανῶς μὲν οὔ—δοκεῖς γάρ μοι συχνὸν ἔργον λέγειν—ὅτι μέντοι βούλει διορίζειν σαφέστερον εἶναι τὸ ὑπὸ τῆς τοῦ διαλέγεσθαι ἐπιστήμης τοῦ ὄντος τε καὶ νοητοῦ θεωρούμενον ἢ τὸ ὑπὸ τῶν τεχνῶν καλουμένων, αἷς αἱ ὑποθέσεις ἀρχαὶ καὶ διανοίᾳ μὲν ἀναγκάζονται ἀλλὰ μὴ αἰσθήσεσιν αὐτὰ θεᾶσθαι οἱ θεώμενοι, διὰ δὲ τὸ μὴ ἐπ᾽ ἀρχὴν [511d] ἀνελθόντες σκοπεῖν ἀλλ᾽ ἐξ ὑποθέσεων, νοῦν οὐκ ἴσχειν περὶ αὐτὰ δοκοῦσί σοι, καίτοι νοητῶν ὄντων μετὰ ἀρχῆς. διάνοιαν δὲ καλεῖν μοι δοκεῖς τὴν τῶν γεωμετρικῶν τε καὶ τὴν τῶν τοιούτων ἕξιν ἀλλ᾽ οὐ νοῦν, ὡς μεταξύ τι δόξης τε καὶ νοῦ τὴν διάνοιαν οὖσαν.

ἱκανώτατα, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ἀπεδέξω. καί μοι ἐπὶ τοῖς τέτταρσι τμήμασι τέτταρα ταῦτα παθήματα ἐν τῇ ψυχῇ γιγνόμενα λαβέ, νόησιν μὲν ἐπὶ τῷ ἀνωτάτω, διάνοιαν [511e] δὲ ἐπὶ τῷ δευτέρῳ, τῷ τρίτῳ δὲ πίστιν ἀπόδος καὶ τῷ τελευταίῳ εἰκασίαν, καὶ τάξον αὐτὰ ἀνὰ λόγον, ὥσπερ ἐφ᾽ οἷς ἐστιν ἀληθείας μετέχει, οὕτω ταῦτα σαφηνείας ἡγησάμενος μετέχειν.

μανθάνω, ἔφη, καὶ συγχωρῶ καὶ τάττω ὡς λέγεις.